We just received the Ig Nobel for researching how wombats poop cubes (spoiler: it’s not a square anal sphincter). We’re still hammering out the details of how this happens.

The story so far…

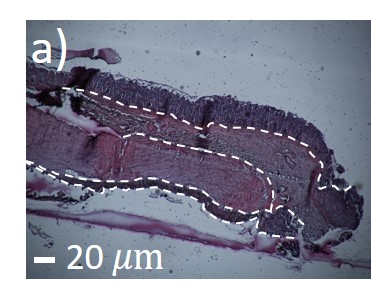

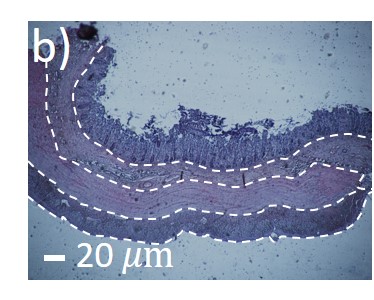

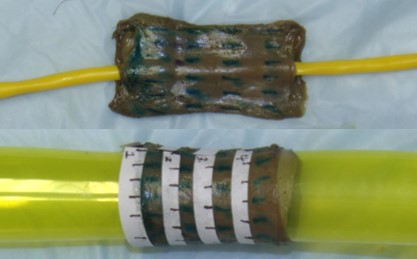

From dissections, we know that the cubic shape of the feces is formed in the last meter of the intestines, known as the distal colon. The histology shows that this muscle tissue varies in thickness along the circumference. Preliminary material testing of these intestines also exhibit periodic stiffness along the circumference. To visualize how this changing stiffness could play a role in forming the cubic feces, we sew mimic wombat intestines from cloth, adding extra sew lines to create regions of increased stiffness. In place of feces, we use sticky styrofoam beads that will keep their shape like feces do, but can also be smushed, also like feces. We find that simply shoving these beads into the mimic intestines does not produce cubes. However, by sewing tabs onto the outside of the mimic, we can pull on the outside of the mimic to imitate muscular contractions, the sort of motions that would push feces through the intestines in the wombat. Preliminary experiments show that when we perform these “contractions”, flat sides and corners form.

Wombat feces reconstructed in 3D

CT scans of the wombat’s anus show that the sphincter is indeed round

- Dissections show that the feces form cubes within the intestines of the wombat

- In the distal colon the muscle tissue thickness varies along the ring of the intestines

- The material stiffness also varies along the ring of the intestines

- This varying stiffness along with imitated contractions creates square shapes in wombat intestine mimics (control intestine on left, varying stiffness intestine on right)

Frequently Asked Questions

How did you come up with studying cubed wombat poop?

We were at a conference presenting our study of defecation. A scientist asked if our theory could explain cubic feces. He said his kid had told him about it. -David

It is fair to say that how wombats produce cubed feces is a bit of a fascination for anyone who has come across them in person. After all, it is kind of unbelievable that an animal produces such geometric shaped feces. I have always enjoyed the colourful hypotheses to explain it (such as feces being squeezed between pelvic bones or a square shaped sphincter), but discovered these hypotheses were incorrect, when I dissected my first wombat, discovering that the cubing formation began in the colon up to one meter from the anus. This led to conversations with Ashley and when David got in contact we really got the ball (or cube) rolling on the research. It has been a lot of fun. -Scott

Could you comment on the importance of the public funding for scientific research?

20% of nobel prizes are from observational discoveries, things that the scientists were not looking for but happened to see.

A lot of interesting things can come from basic research. Without having basic funding, there will be a lot of topics that will go unstudied. Even more, topics such as animal research often have a finite timeline because animals are going extinct. -David

Public funding is absolutely vital to keeping scientific research going, in that it gives researchers the actual opportunities to do their work, but even more importantly, it ensures that science is accessible to the public. Researchers who receive public funding have an obligation to then ensure that their work makes it’s way back into the public space, and that the science that’s being done isn’t just locked up in scientific journals for only other scientists to look at. It’s extremely important that all members of our society are science-literate and one of the ways that scientists can help with this is to take the time and effort to communicate their science to people who might not necessarily have a science back ground or training, and to make sure that it’s able to be understood by everyone. This will help us to have a much more science-literate society. -Ashley

Have you made any money with your research? What are the possible future applications?

No money yet.

We are writing a grant to look at how animals communicate to each other with cubic feces. We’re interested in how such interesting properties evolved in a soft intestine. We also think there might be medical applications. When there are diseases to the colon, its material properties can change, and that might change the shape of feces. Maybe doctors or veterinarians can say something about an animal’s health if they see angular edges or flat faces in their feces. -David

People

Meet the people working on this project

David Hu – Professor of Mechanical Engineering at Georgia Institute of Technology

Scott Carver – Professor of Biology at University of Tasmania

Patricia Yang – Mechanical Engineering Researcher at Georgia Institute of Technology

Ashley Edwards – Biology Researcher at University of Tasmania

Miles Chan – Mechanical Engineering Researcher at Georgia Institute of Technology

Michael Kowalski – Biomedical Engineering Researcher at Georgia Institute of Technology

Kelly Qiu – Biomedical Engineering Researcher at Georgia Institute of Technology

Alynn Martin – Biology Researcher at University of Tasmania

Alex Lee – Biology Researcher at Georgia Institute of Technology